You get to a certain point in life where you start to look back on certain things with a certain philosophical detachment. I’ve come to realize something tonight (sitting at my favorite table at the China Pavilion in Lisbon musing over life’s mysteries with a Maker’s Mark Manhattan).

Evidence of a life well lived is when you regret the things that you’ve done more than you regret the things that you haven’t done. It does not work that way when it comes to evidence of a portfolio well-invested.

Have you ever noticed that reptiles all look like they are constantly smiling? It’s probably because they don’t do much and therefore live relatively regret-free lives. True, reptiles do make for pretty dull pets, but they just seem so content and serene (particularly while digesting a beady-eyed, frenetic furry little scampering animals that used to say squeak). Investors can learn a lot from lizards and snakes. I’m certainly not too proud to admit that I have learned (slowly, repetitiously and expensively) that the more I do, the more scuffling noises I make, with a twitching little wet nose and fluttering heart rate, the more frequently I find myself becoming digested by that most cold-blooded, unblinking predator of them all. That one that we call “the stock market.”

My friends, I’ve been an investor for over 25 years during which time I have found far, far more ways to lose money than I have found ways to make money. If I had to distill this tidbit of hard-won wisdom into just one sentence, it would be this: dull pets make for better pets, and dull investments make for better investments. Other smarter and more successful investors than I may disagree strongly with that statement, but having learned (slowly, repetitiously and expensively) that I am not as smart as those investors, I now confine myself to making money in one of the few ways that I seem capable of. To wit, I prefer to invest in industries where nothing is really going on. And then do virtually nothing for the next 20 or 30 years.

The key – the absolute key – to being able to successfully not do anything is that I genuinely don’t care if other investors make more money than me. It took years to master that particular skill. And the other key is if you’re planning to just lay out basking in the sun, don’t do so on a highway of speeding ten-ton trucks. Can an investor actually do nothing for 30 years if the investor owns an innovative company in a hot and competitive industry? I don’t know. I’ve never tried and can’t say I’m anxious to do so. But what about an industry that is somewhat immune to change and innovation? Now we’re wading into my favorite little corner of the capital market swamp. When it comes to boring, ignore-me industries, I have seven favorites: (1) chocolate, (2) scents and flavorings, (3) house paint, (4) trains, (5) water utilities, (6) lubricants, (7) diapers, tampons and toilet paper.

Yawn. Hershey’s might roll out a white chocolate Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup once in a while, and maybe Old Bay Seasoning might come in a slightly different shaped box, but other than that not much is going on there. 20 years from now, I doubt very much that we’ll all be eating E-chocolate or downloading E-seasoning onto our E-chickens. What will a high tech diaper look like in 30 years? I neither know nor want to know. And when it comes to novelty and innovation, it’s a safe bet that the water that comes out of your kitchen faucet isn’t going to get piped to your house in any sort of innovative, disruptive new way. Certainly, not one that I can think of.

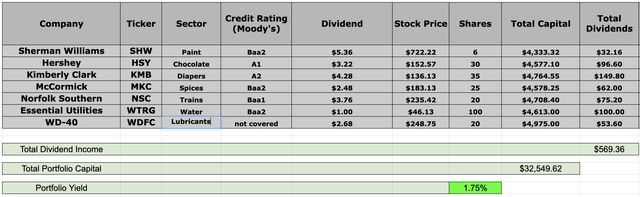

So what if you want to just go all-out-petrified-turtle on your portfolio? Here are seven companies that I own for this very purpose. I proudly call this “The hibernating reptile portfolio,” comprised of some of the most dominant names in the most yawn-inducing industries I can think of. Sherwin-Williams (SHW), Hershey (HSY), Kimberly-Clark (KMB), McCormick (MKC), Norfolk Southern (NSC), Essential Utilities (WTRG) and WD-40 (WDFC). In the attached chart I include the dividend data (which I pulled from Seeking Alpha) because sitting back and doing nothing besides reinvesting dividends year in and year out strikes me as a highly reptilian undertaking. And let’s not skip that credit rating! Companies with sub-investment grade debt can get real interesting real quick. Us lizards don’t like that.

(Source: Author’s spreadsheet using data from Google Sheets, Moody’s and Seeking Alpha).

Did I neglect to leave off the price earnings ratios? Here is my thought if you are going to hold stock in a company for 30 years and reinvest dividends. Sometimes when you reinvest dividends into more shares over the next few decades, you will overpay. Other times when you reinvest, you’ll get a bargain. After two, three or maybe four decades, it will all balance out and if it doesn’t, you probably won’t either care or remember what you originally paid for the stock.

It’s statements like this that drive value investors completely nuts – which I understand because I am sort of a value investor too. But I’m also friends with people in their 80s who have owned shares in certain companies for 50 to 60 years and they all tell me the same thing. They don’t know what they originally paid for the stock and don’t care. Maybe we can learn something valuable from that – assuming that we (or our heirs) have long investment horizons.

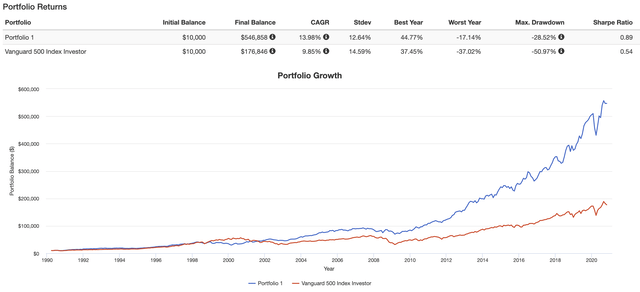

Do you know what else some people really hate? They hate backtesting. Survivorship bias just makes them want to scream… which I’m sorry to say can be ever so entertaining and fun for the rest of us! Oh, especially those of us giving some serious thought to ordering a second Maker’s Mark Manhattan. Fun is why I specifically decided to backtest an equal weighted portfolio comprised of the hibernating reptile portfolio.

(Source: PortfolioVisualizer.com)

How did the hibernating reptile’s portfolio fare against the S&P 500 over the past 30 years? The answer is that it’s 300% higher. And as much as some of us dislike picking 7 known winners and backtesting to see how much money we could make if only we had a time machine, there actually is utility when it comes to looking at past performance: there is no other way that I know of to calculate a portfolio’s Alpha than to look at past performance. Now given the fact that you happen to be reading an article on a website with the word “Alpha” in the name, you may be curious to know that for the past 30 years, the hibernating reptile racked up annualized Alpha of 8.68% according to PortfolioVisualizer.com.

Will the hibernating reptile garner 8.68% Alpha in the future? I don’t know, but I’ll tell you what I’m going to do while I wait to find out:

“Oh waiter, I’ll take another one please!”

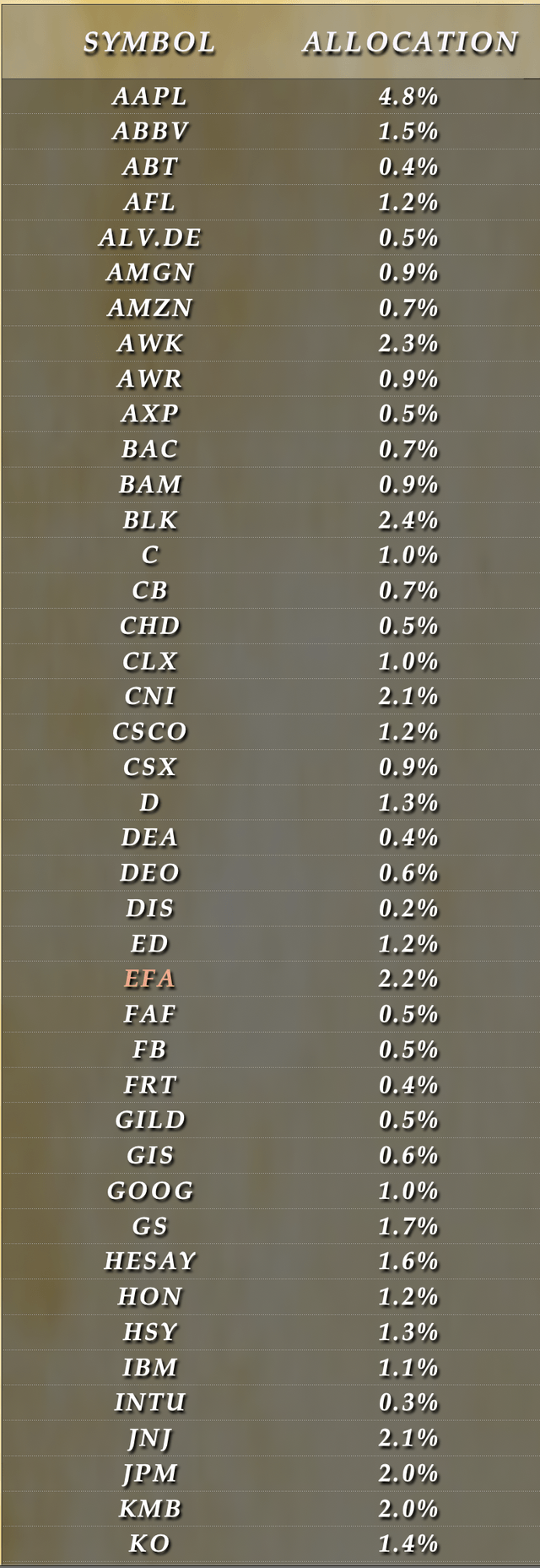

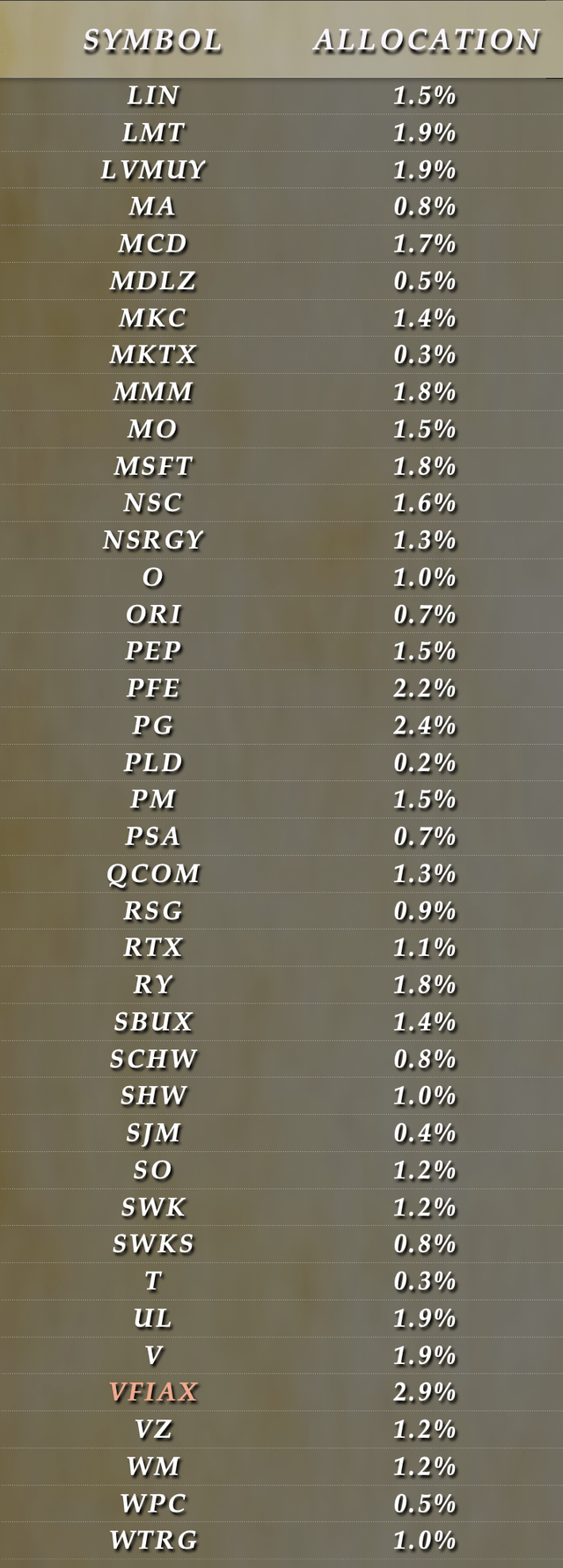

As an aside, what am I doing with my real world portfolio these days? Reinvesting dividends. Enjoying the market’s rotation back into stodgy but higher yielding companies such as REITs, utilities and consumer staples other than Clorox (CLX). I sold my shares of WD-40 which was probably stupid but the stock surged from $200 to $250 and I got antsy. Not very reptilian of me, and in 10 years when the stock is 1,000% higher I’ll probably feel like an idiot.

My current portfolio is comprised thusly:

Not that I think any of that is actionable or even relevant to you… other than to disclose my conscious and unconscious biases. I will underscore one obvious bias which is that I happen to own six out of seven of the hibernating reptile’s favorite meals, but I do tend to eat my own cooking when I write about investing.

Disclosure: I am/we are long SHW,NSC,HSY,MKC,KMB,WTRG. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: I am not an investment advisor and nothing in this article constitutes investment advice. I have no idea, literally no idea, whether you should or should not buy, sell, not buy, or not sell any stock or fund mentioned or discussed in this article. I write about what works for me and what doesn’t, which may or may not give you your own ideas about what might or might not work for you.